So, you read about infodumps, and now you want ideas on how to avoid them? Great.

So, you read about infodumps, and now you want ideas on how to avoid them? Great.

This list is NOT all inclusive, but it’s a start.

Break up the characters.

Do you need to introduce more than one or two at a time? Sometimes you do, and that’s fine. But when you do…

Give appropriate information.

I read a published novel, and every time the author introduced a character, she gave the dossier—name, approximate age, height and weight.

This can be relevant if you’re dealing with aliens or fantastical races, but if you’re dealing with humans, the information can be introduced later at more appropriate times.

Instead of saying, the woman was about five-foot one and a hundred and fifty pounds, describe the scar across her face, or the fight that left her limping for the rest of her life. This gives your characters dimension—she’s more than her height and weight.

Describe organically.

In other words, let it just be natural.

When people meet someone for the first time, they may notice height and weight, but they notice other things, too. Voice, smile, teeth, eyes, nose, ESPECIALLY when these characteristics are abnormal. You can have ten underweight characters, but only one of them will have a voice poisoned by a lifetime of cigarettes.

Delete what doesn’t belong.

I said it before—I don’t care about where a cashier got her tattoo unless it adds to the plot (a place being investigated for using pig’s blood as pigment, or illegal/governmental/cult branding). Otherwise, yeah, I don’t care.

Choose better descriptions.

Instead of saying a chair lay on its side after a ruckus, you can say overturned chair. Instead of saying, a yellow bucket chair with brown stripes and a green outline of a naked woman, a seashell lamp, and a red and black plaid couch, you can say, the seventies called and want their furniture back.

Some precise descriptions are fun to write and fun to read, but you’ve got to know when and where.

Avoid repetition.

Okay, remember the published book that introduced each character by the dossier? Yep, by the third character, I skipped lines until the moment where I just stopped reading altogether.

This is a dangerous position to put a reader in. She is an established writer with a loyal fan base, and while she “earned the right to publish newbie no-nos” in theory, it may have cost her part of her existing readership, as well as any future newcomers who haven’t read the other titles that won her audience. My point is not to tear the writer down, but to tell you, dear aspiring/established author, how you can best keep my (and other first-time readers’) attention.

Scatter the info.

Remember in infodump where you walked into my cabin and found out everything there was to know about it in that one scene?

Welp, I listened to my critique partner. She didn’t need to see the brown micro fiber loveseat by the fireplace, or the curved leather couch with entertainment system in the den, the kitchen sink, or the study.

My MC will eventually sit on the couch. She can touch the micro fiber then. Or drop a glass in the one-basin sink.

Be concise.

You’ve got 5 men. One plowed fields his entire life, another diagnoses anything from flus to hemorrhoids, the third breeds a healthy strain of livestock, the fourth makes so many calculations in a day, he doesn’t need a calculator and the fifth likes cookies and milk and the color red.

You’ve got 5 men. An agriculturalist, a doctor, a farmer, an accountant and Santa. (And a reader who wasn’t tempted to skim.)

A red-and-white-striped peppermint candy. Uh, you mean a candy cane?

There are clever ways of describing something, but sometimes it’s better to keep it simple. Know when to be clever and know when your readers will only cross their eyes in confusion.

Be clever when you’ve already used the word on the page, be concise if your word count is pushing 110,000.

And for the love of everyone subjected to the story, do NOT get clever to boost word count. Word count should be focused on pretty words that move plot and characterization forward, not scarce plot and characterization held together by the skimpy fabric of pretty (but empty) words plastered in between.

Get another opinion.

Ask a friend to read your work. This person doesn’t need to be a professional editor or critic, this person just has to be a reader. After all, readers buy the book, and liking a novel or hating one requires no expertise at all. People who read a lot know when things feel forced or unnatural, when something isn’t clear, when there’s too much or too little information, or when they’re bored. A good reader who gives honest feedback is one of the best things you can have in your literary arsenal.

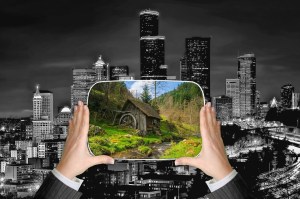

Imagery is an important part of setting, which is one of the 5 elements of a story.

Imagery is an important part of setting, which is one of the 5 elements of a story.

So, you’ve written a great novel, you love the voice, but then you read someone else’s and realize how terrible yours is. Or, is it?

So, you’ve written a great novel, you love the voice, but then you read someone else’s and realize how terrible yours is. Or, is it? So, you read about

So, you read about  So, you’re reading a great passage and really like the writing. You’re eager to get to the second paragraph, and then it happens. So. Many. Details.

So, you’re reading a great passage and really like the writing. You’re eager to get to the second paragraph, and then it happens. So. Many. Details.

You must be logged in to post a comment.